Every other Thursday, Brian goes out of this world, waxing recommendatious on great reading that will transport you to fantastic, far-away worlds and times. Looking to escape? Escape Velocity is your bi-weekly ticket!

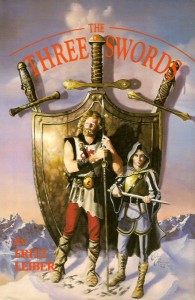

In 1989, the Science Fiction Book Club published all the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories in a massive two-volume omnibus, of which The Three of Swords was the first half.

Fantasy doesn’t have to be epic to be great reading. Today’s case in point: Fritz Leiber’s long-running series of stories about Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

Say the words “fantasy story” these days and most people will likely think of the ginormous fantasies of J.R.R. Tolkien, George R.R. Martin and their countless imitators and followers. The shelves of (the few remaining) bookstores are overrun with multi-volume, multi-thousand-page series that depict in painstaking, soap-opera detail a lowly street urchin’s discovery that they possess great power because they are in fact their world’s prophesied Chosen One, and their subsequent massive struggles against the forces of tyranny, darkness, and more-or-less-ultimate evil.

(Don’t get me wrong, I love those ten-doorstop-sized-volume series as a general rule, and I know more than one of them will get a shout-out in this column.)

But, as the title of their debut story states, “Two Sought Adventure”—for almost fifty years, Fafhrd the northern barbarian and the wizard’s apprentice-turned-rogue the Gray Mouser were the all-too-believable stars of a succession of tales that were consistently inventive, exciting, and even, often, very funny. Come, let me introduce you to the two greatest fantasy heroes you’ve likely never heard of.

In the mid-twentieth century, before Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings became the standard-bearing template we know today, stories of magic and adventure in more-or-less medieval-ish settings coalesced into the fantasy genre in the pages of magazines like Weird Tales, Fantastic, and Unknown, and as often as not those stories were what we would now call “sword and sorcery.”

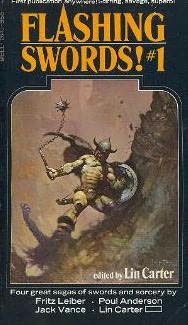

Sword and Sorcery distilled: the first Flashing Swords! anthology edited by Lin Carter (This 1973 volume also contained the first publication of the Lankhmar story “The Sadness of the Executioner”)

The protagonists of these tales aren’t long-lost princes or unwitting messiahs, and the focus isn’t on the scheming intrigues of the highborn or the last stand of good against ultimate evil. No, these “heroes” tend to be more morally ambiguous adventurers, wanderers who live by their swords and fight to escape the clutches of a scheming sorcerer or escape an exotic city with their lives (and possibly treasure) intact.

Robert E. Howard’s Kull the Conqueror and, later, Conan the Barbarian were the first popular ongoing characters, and many followed in their wakes: Michael Moorcock’s moody, albino anti-hero Elric of Melniboné; David Gemmel’s Druss the Legend and the long series of associated novels set in the larger Drenai setting; Catherine (C.L.) Moore’s Jirel of Joiry, the first sword-and-sorcery heroine; and Clark Ashton Smith’s extremely strange Conan-meets-Lovecraft “Hyperborean Cycle.”

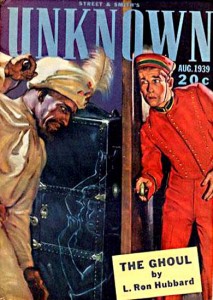

It was in the August 1939 issue of Unknown (the fantasy and weird fiction sister magazine to editor John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction), ten years after Conan’s print debut, that the world met two very different fantasy heroes. In “Two Sought Adventure,” a red-haired northern barbarian named Fafhrd and his cunning sneak-thief friend called the Gray Mouser sought out a treasure hidden in a mysteriously deserted stone house in a forest.

More stories followed, fleshing out the pair, the city of Lankhmar in which many of their adventures are set, and the larger world of Nehwon. Between magazines, anthologies, and original stories written for the “definitive” paperback collections that were published starting in 1968, a total of 37 stories saw print, the last being the novella “The Mouser Goes Below” in 1988. There was also the full-length novel The Swords of Lankhmar in 1968 (an expansion of the 1961 story “Scylla’s Daughter,” itself an update of a very early Lankhmar story that pre-dated the pair’s 1939 debut). (Leiber died, aged 81, in September 1992.)

The August 1939 issue of Unknown, in which Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser made their debut

As was Leiber’s stated intention, the romantic-but-pragmatic Fafhrd and the cynical-with-a-heart Mouser were more recognizably human kinds of characters than the scowling, violent, blood-and-thunder warriors of Robert E. Howard and his earlier contemporaries. Fafhrd and the Mouser joked and bantered, they made mistakes, they fooled their adversaries, and they had their hearts broken. Reading a Conan story is like sitting around an ancient campfire hearing the tribe’s elder recount a thrilling legend of gods and heroes. Reading a Lankhmar story is like going there, smelling the smoke-filled taverns and filthy alleyways, meeting colorful people that live and breathe. (Again, I’m not disparaging Conan and the other sword-and-sorcery heroes, I’m merely pointing out via contrast how Leiber innovated a more immediately relatable flavor of this versatile genre.)

It was only after many years and many published stories that we learned the origins of our two slightly soiled and worn heroes. In “The Snow Women,” first published in the April 1970 issue of Fantastic, a traveling dancer from the south offers a way for the young barbarian Fafhrd to escape his predestined future in the northern Cold Waste, but his plans incur the wrath of his mother, his bride, and the other women who dominate the frozen land. Meanwhile, in “The Unholy Grail” (Fantastic, October 1962), we learn that the Gray Mouser was once a young wizard’s apprentice named Mouse, whose world is destroyed when a cruel lord murders his master. The two young adventurers first meet in the magnificent, tragic novella “Ill Met in Lankhmar,” which won a richly deserved Hugo award after its first publication in the April 1970 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Those three stories form the 1970 collection Swords and Deviltry, which is chronologically the first of the seven book series that most often collects Leiber’s Lankhmar stories. (Check out the series’ Wikipedia page for the complete set.) I started there and read the stories in order of their internal chronology, but since the stories were originally published very much out of order, you could probably jump in anywhere and enjoy yourself thoroughly.

The influence of Leiber’s duo is far-reaching. Along with Jack Vance’s stories of the Dying Earth, Leiber’s Lankhmar tales were one of the main conceptual influences on the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game, and via D&D they influenced a whole new generation of fantasy stories from the 1980s on. Trust me, if you’ve read much fantasy at all over the last thirty years, you’ve read something that was informed somewhere along the line by Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

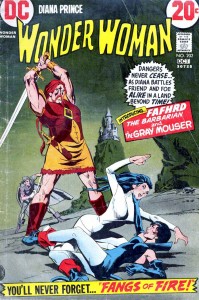

Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser make their comic book debut in Wonder Woman #202, October 1972

Perhaps most unexpectedly, Fafhrd and the Mouser turned up in Wonder Woman #202 (October 1972), the first of two issues that were written by prominent science fiction novelist Samuel R. Delany, before starring in their own short-lived DC series called Sword of Sorcery. Howard Chaykin and Mike Mignola later produced another short-lived series of comic adaptations for Marvel’s Epic Comics imprint in 1990 and 1991, the trade paperback collection of which was released by Dark Horse in 2007.

Meanwhile, thinly-disguised but very recognizable versions of the pair have turned up in Marvel’s Conan comics, DC’s Fables, and Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels.

But pound-for-pound, the most enjoyable iteration of the duo remains the original canon of Fritz Leiber stories, which also make a case for being the most enjoyable product of the entire sword-and-sorcery genre. Sadly, as of this writing some of the collections are out of print, but the series has been going in and out of print periodically since their initial publication, so they might soon be available again. Electronic editions are currently available both for the Kindle and in other formats through Fictionwise. However you gotta get ’em, I can unreservedly recommend doing so—Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser will deservedly (and characteristically) live large in your imagination for a long time.

The “Flashing Swords” cover looks like a Frank Frazetta!