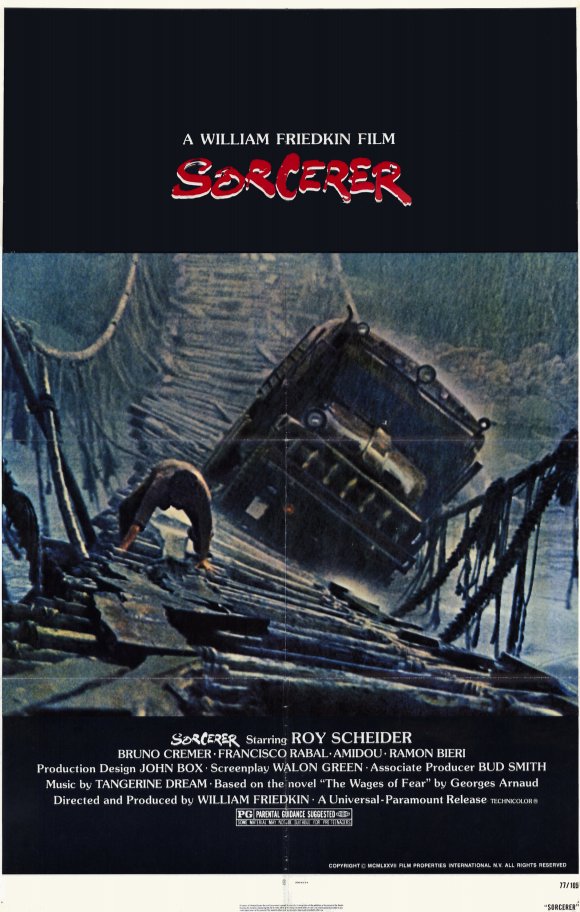

I was lucky enough to attend a very small screening of William Friedkin‘s rarely-shown 1977 cult classic Sorcerer, a remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot‘s French classic Wages of Fear, which has been called the most suspenseful film of all time. What made this screening such a treat was not only seeing a 35mm print of Sorcerer, but the rare Q&A by the director Friedkin himself which was held afterward.

Fans of the film will immediately understand what is so special about this event, since is that Sorcerer is out of print and hardly (if ever) screened or talked about anywhere except on small fan blogs. For Sorcerer fans, and Friedkin fans in general, this was an ultra-super-rare discussion of a film that is now, thanks to a lawsuit won by the director against Universal and Paramount Pictures, again able to be screened in public. Much to the delight of said fans, it will also see a Blu-ray release at the end of this year. (F**K YEAH!)

As fans of the Podwits know, Sorcerer is one of my top 10 movies of all time, and since little to nothing about it is available online, I made it my mission to make this Q&A available to everyone who was unable to attend the May 2 screening. Friedkin spoke about Sorcerer and who the script was originally written for (WOW!), Cruising, The Exorcist, The French Connection, Tony nominees Carrie Coon and Tracey Letts (the Pulitzer-winning writer of Bug and Killer Joe), and friend-of-the-Podwits Randy Jurgensen. He also spoke about the controversy the year he produced the Academy Awards, his thoughts about film and filmmaking, and much more. It really is a must-read for any William Friedkin fan!

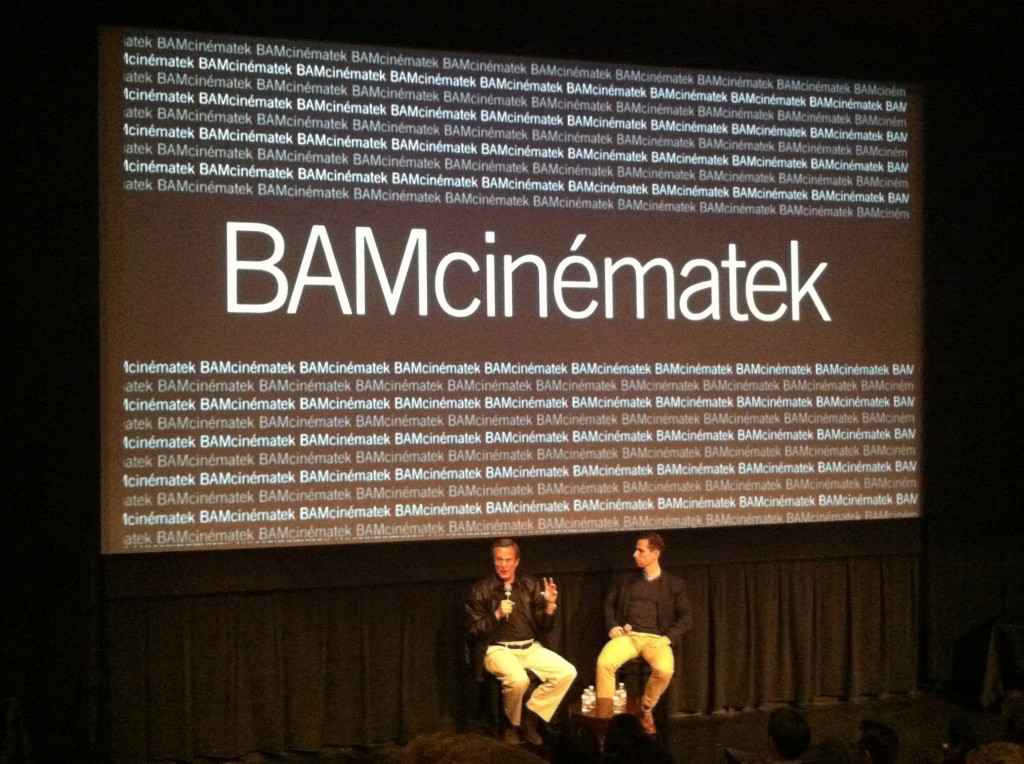

William Friedkin & moderator Scott Foundas

The screening was held at BAM, and was moderated by film critic Scott Foundas. Friedkin also has a new memoir out in hardcover, called The Friedkin Connection, which is also a must-read for any cinemaphile or fan of the director.

Here is what went down:

William Friedkin: Thank you very much. Thank you to Scott Foundas and thank you to the Brooklyn Academy of Music for hosting this screening and thank you all—I really appreciate it. Thank you- Goodnight. (Big laugh) Scott?

Scott Foundas: How are you?

WF: Not too bad.

SF: Let’s start because there’s just a nice, large dedication to Henri-Georges Clouzot at the end of the film. Just talk a little bit about your discovery of Clouzot’s work and when you first saw his version of the film and when you thought about remaking it?

WF: I first saw it in the late ’50s at a revival and it was very—obviously impressive, it was one of the greatest films ever made, Clouzot’s Wages of Fear. And it wasn’t until many years later after I had finished The Exorcist that I started to think about what I might wanna do next, and it occurred to me at that time, this was in the middle ’70s, when America had just come through a national nervous breakdown, after the assassinations, the Vietnam war, and it seemed to me—I guess it’s always ever thus—that the world was full of strangers who hated one another, but if they didn’t cooperate, if they didn’t work together in some way, they would blow up. And this film seemed to me to be a metaphor for that idea, which I thought was a valid theme then, and now. I think it’s possibly worse now, with so many countries have weapons of mass destruction. And so, it was the theme that attracted me. So I went to Clouzot in Paris, he was not well at the time. I loved his films, especially Wages of Fear and Diabolique, and guys know Diabolique? If you don’t know Diabolique, then get the hell out of here! (big laugh) And I said I would be interested in remaking his film or doing a new version, and he said “Okay, but do you think anything’s wrong with mine?” I said “No, in fact, I would love to get your film released, but I can’t get a major studio to re-release it in theaters.” It was a very limited audience for Wages of Fear in America, you know, it was a foreign film, the people who saw it loved it, and I said “I’d like to do a new version of it that would only use the basic premise and your theme.” He said “Okay, but I don’t own the rights” and I said “Really?” He said “No, the fella who wrote the novel, Georges Arnaud, owns the rights and we don’t speak. He doesn’t talk to me.” You know it was one of those relationships like, like the Beatles, I guess. They had made magic together and then they weren’t talking to each other. So we went to Georges Arnaud’s home through his attorney, and he was very pleased to have this done because he didn’t like Clouzot’s film (laugh), if you can believe that and it’s true. So we got the rights, and I set out to make the film- Wally Green and I had worked to together in documentaries, he also wrote The Wild Bunch—you know The Wild Bunch? (laughter and applause) And we thought out ways we could keep this theme, but do all new events and have new characters and have new back stories that got them there. And we made the decision that these guys were not going to be heroes, let alone superheroes. These were bad guys and I felt I could take an audience through this with not the most likable people on Earth, and I guess I was wrong. (Big laugh) Shit happens, you know? (big laugh)

WF: I first saw it in the late ’50s at a revival and it was very—obviously impressive, it was one of the greatest films ever made, Clouzot’s Wages of Fear. And it wasn’t until many years later after I had finished The Exorcist that I started to think about what I might wanna do next, and it occurred to me at that time, this was in the middle ’70s, when America had just come through a national nervous breakdown, after the assassinations, the Vietnam war, and it seemed to me—I guess it’s always ever thus—that the world was full of strangers who hated one another, but if they didn’t cooperate, if they didn’t work together in some way, they would blow up. And this film seemed to me to be a metaphor for that idea, which I thought was a valid theme then, and now. I think it’s possibly worse now, with so many countries have weapons of mass destruction. And so, it was the theme that attracted me. So I went to Clouzot in Paris, he was not well at the time. I loved his films, especially Wages of Fear and Diabolique, and guys know Diabolique? If you don’t know Diabolique, then get the hell out of here! (big laugh) And I said I would be interested in remaking his film or doing a new version, and he said “Okay, but do you think anything’s wrong with mine?” I said “No, in fact, I would love to get your film released, but I can’t get a major studio to re-release it in theaters.” It was a very limited audience for Wages of Fear in America, you know, it was a foreign film, the people who saw it loved it, and I said “I’d like to do a new version of it that would only use the basic premise and your theme.” He said “Okay, but I don’t own the rights” and I said “Really?” He said “No, the fella who wrote the novel, Georges Arnaud, owns the rights and we don’t speak. He doesn’t talk to me.” You know it was one of those relationships like, like the Beatles, I guess. They had made magic together and then they weren’t talking to each other. So we went to Georges Arnaud’s home through his attorney, and he was very pleased to have this done because he didn’t like Clouzot’s film (laugh), if you can believe that and it’s true. So we got the rights, and I set out to make the film- Wally Green and I had worked to together in documentaries, he also wrote The Wild Bunch—you know The Wild Bunch? (laughter and applause) And we thought out ways we could keep this theme, but do all new events and have new characters and have new back stories that got them there. And we made the decision that these guys were not going to be heroes, let alone superheroes. These were bad guys and I felt I could take an audience through this with not the most likable people on Earth, and I guess I was wrong. (Big laugh) Shit happens, you know? (big laugh)

SF: Well talk a little bit about the casting because I was thinking tonight, in a way this is a little like Inglorious Bastards, Avon La Letra, you know where you have foreign stars speaking partly in their own languages, uh, certainly marquee names, Amidou, Francisco Rabal, and the great Bruno Cremer with an arc that convinced the two studios that financed this film to let you go that way, instead of having American character actors playing those parts.

WF: No, After The Exorcist, I could have filmed my bar-mitzvah (Big laugh). As the headline read in the New York Times this morning, “I thought I was bulletproof and so did they.” So I had 2 studios vying for the film, Paramount and Universal, and originally, Wally and I wrote the script for Steve McQueen. We wrote it for Steve, we talked to Steve about it. When we finished we sent Steve the script and while Steve was reading the script we went to Marcello Mastroianni and um, uh- and Lino Ventura, who was a gigantic French star, and Mastroianni of course was a star of some many of Fellini’s films. And they agreed to do it—with Steve McQueen. So now, uh, Steve calls me and says “This is the best script I’ve ever read,” he said, “I’m in, I wanna do this.” He said “I need a favor from you,” and I said “What’s that?” and he said “You know I just married Ali,” (he had just married Ali MacGraw), he said, “I know you’re going to be out somewhere shooting in some far off place, and I can’t take her to that place and have her just hang around, you know as my wife…” He said, “why don’t you write a part in there for her?” (Laugh) And I said “Well-“

SF: It could have been her at the end there in the cantina…

WF: You know I never thought of that… (big laugh) Well she wasn’t right for that role, so uh, I said, “You just told me this was the best script you ever read, and there’s hardly a major role as a woman…” and he said, “Ok, [how about] making her an associate producer or something, so she can be with me.” And I was extremely arrogant at that time and I said “We don’t have associate producers who don’t do anything, (laugh) we’re not going to make her an AP.” He said ok, to that he said, “find someplace in America to shoot it.” And I had already scouted locations that I had fell in love with, and I said “I’m not going to shoot it in America, the part of making this film is going to be an adventure, in several countries and that’s it.” He said, “Billy, I can’t do the film then.” And I said, “Ok, next case.” And it was only a week later that I realized a close up of Steve McQueen was worth the greatest landscape you could find. Um, and if I had it to do over, and as great as Roy is in this film, it was written for Steve McQueen, and when I lost Steve, I lost Mastroianni– for another reason- he had had a child with Catherine Deneuve, and she said if you go off to do this picture for as long as they want to do it, I’m not going to have your daughter with you. So he dropped out, and then Ventura dropped because he didn’t want to take second billing to Roy.

SF: Maybe if you made Catherine Deneuve and associate producer on it… (big laugh)

WF: Why Not?! Listen, today I would do it! I was extremely arrogant in those days, and filled with hubris, and I thought the film was about me- (laugh) – not the cast. I thought when an audience sees my name above the title, they’re in, they’re there…

SF: There is another quite amazing story about this movie that you tell in your wonderful memoir, which you are going to be signing later tonight, which is that when the studio asked you to shoot some insert shots of the odometers on the trucks, what did you tell them?

WF: Well, I told you already I was arrogant, (laugh) I was called into a meeting with the heads of Paramount and with the heads of Universal, a guy named Sid Sheinberg and Barry Diller. And they asked me to come to meet with them; they wanted to give me some notes; the wanted to help the director. And so I thought what the hell could these guys tell me? So I said, if you’re going to give me notes, I want to bring my writer and my film editor into this meeting. And they didn’t like that because they didn’t like dealing with the guys who really made the film, they wanted to deal with ‘above the title’ guys. I said no, I wanna have my writer and editor; both editors there, the editor and his assistant. And they reluctantly agreed. So then I told Buck Smith, the editor, and Wally Green, and the assistant editor, Ed Humphreys, I’m going to take you into this meeting, into the private dining room at Universal, and they’re going to give notes. And he’s what I want you guys to do… Don’t shave the night before. Wear your shirt buttoned incorrectly, wear mismatched socks, walk in with your shoes untied and then when you sit down, don’t react to anything I say or do. (Laughing) No reaction, and when they’re talking, just stare at them, like this- (laugh) Don’t nod your head, when they’re making these suggestions, don’t go ya, or take notes or anything, just stare at them as though they are from Mars or something. (laugh) And that’s what we did. The lunch order comes around, waiters in black tie and stuff, and everyone ordered an iced tea to start with, and I ordered a bottle of Smirnoff. (big laugh) And they started in with their notes, and they were surprised because I told the waiter, I don’t want a glass. So while they’re sipping their iced teas, and getting together their notes, I opened the bottle and I started to drink from the bottle. And they didn’t say anything, they just started giving us notes. We just stared at them. And then about 10 or 15 minutes into this, I fell out of my chair and fell on the floor. I wasn’t drunk, I had a high tolerance for alcohol, I just fell on the floor, and they didn’t say anything. (Big laugh) After a few more minutes, they turned to Wally Green, and said, “Does this happen often?” And he said “Everyday.” (Big laugh) The notes went by, the meeting was over, I had my guys carry me out of there and then I thought about- I said to them, look, I don’t shoot inserts, I’m not going to make inserts of the odometers- well, unless, I said to Mr. Diller, you want to sent me back to Mexico to shoot some inserts of the truck. He said No, no, no- nevermind, and it’s ok. But then I thought they were right, and I actually shot the inserts (Big laugh). We shot the inserts on the back lot of Universal. I thought they were right, but that was my reaction to my notes. (big laugh) No quarter given. Remember, in order to succeed in those days, you had to make the heads of the studios, in order to let you alone, you had to make them think you were psychologically unsettling. You had to make them believe you would of anything. So they basically didn’t bother with me, because I did that on The Exorcist, you know, they thought I was so nuts, that they just let me alone. They figured, if there was a problem, and I imploded, the film would implode too. So that was a strategy I had active in those days.

WF: Well, I told you already I was arrogant, (laugh) I was called into a meeting with the heads of Paramount and with the heads of Universal, a guy named Sid Sheinberg and Barry Diller. And they asked me to come to meet with them; they wanted to give me some notes; the wanted to help the director. And so I thought what the hell could these guys tell me? So I said, if you’re going to give me notes, I want to bring my writer and my film editor into this meeting. And they didn’t like that because they didn’t like dealing with the guys who really made the film, they wanted to deal with ‘above the title’ guys. I said no, I wanna have my writer and editor; both editors there, the editor and his assistant. And they reluctantly agreed. So then I told Buck Smith, the editor, and Wally Green, and the assistant editor, Ed Humphreys, I’m going to take you into this meeting, into the private dining room at Universal, and they’re going to give notes. And he’s what I want you guys to do… Don’t shave the night before. Wear your shirt buttoned incorrectly, wear mismatched socks, walk in with your shoes untied and then when you sit down, don’t react to anything I say or do. (Laughing) No reaction, and when they’re talking, just stare at them, like this- (laugh) Don’t nod your head, when they’re making these suggestions, don’t go ya, or take notes or anything, just stare at them as though they are from Mars or something. (laugh) And that’s what we did. The lunch order comes around, waiters in black tie and stuff, and everyone ordered an iced tea to start with, and I ordered a bottle of Smirnoff. (big laugh) And they started in with their notes, and they were surprised because I told the waiter, I don’t want a glass. So while they’re sipping their iced teas, and getting together their notes, I opened the bottle and I started to drink from the bottle. And they didn’t say anything, they just started giving us notes. We just stared at them. And then about 10 or 15 minutes into this, I fell out of my chair and fell on the floor. I wasn’t drunk, I had a high tolerance for alcohol, I just fell on the floor, and they didn’t say anything. (Big laugh) After a few more minutes, they turned to Wally Green, and said, “Does this happen often?” And he said “Everyday.” (Big laugh) The notes went by, the meeting was over, I had my guys carry me out of there and then I thought about- I said to them, look, I don’t shoot inserts, I’m not going to make inserts of the odometers- well, unless, I said to Mr. Diller, you want to sent me back to Mexico to shoot some inserts of the truck. He said No, no, no- nevermind, and it’s ok. But then I thought they were right, and I actually shot the inserts (Big laugh). We shot the inserts on the back lot of Universal. I thought they were right, but that was my reaction to my notes. (big laugh) No quarter given. Remember, in order to succeed in those days, you had to make the heads of the studios, in order to let you alone, you had to make them think you were psychologically unsettling. You had to make them believe you would of anything. So they basically didn’t bother with me, because I did that on The Exorcist, you know, they thought I was so nuts, that they just let me alone. They figured, if there was a problem, and I imploded, the film would implode too. So that was a strategy I had active in those days.

SF: Didn’t you also tell them they could just change the names of the actors if they didn’t like the foreign country names… (laugh)

WF: Ya! At one point Sid Sheinberg saw the ad for the movie and he said “Look at all these foreign names…” And I said “Ya…” I said, “Would you like me to have them change their names? Instead of Francisco Rabal, I could have Frank Rowbuels, or something.. (big laugh) whatever the hell you want, no problem.”

SF: Um, I wanted to ask you about choosing the great Tangerine Dream to do the music for the film and maybe also your ideas about music in film, because really none of your movies have what we call a sort of traditional film score. They have- In To Live and Die in LA you have a suite of songs by Wang Chung, you have the, you know, Mike Oldfield tubular bells in The Exorcist, and you had commissioned a score for The Exorcist that you threw out by Lalo Schifrin, so what are you- what are your- what are you thinking about when you are thinking about what the sound of the movie should be, and why was Tangerine Dream right for this one?

WF: For the most part, not only does the story or the script find me when I am least looking, but the music does as well. And when I was on tour across the world for The Exorcist, one of the people from Warner Brothers in Hamburg or Munich took me out to the Black Forest, to an abandoned church, where this band, The Tangerine Dream was playing after midnight; and there were no lights… except for the electronic lights from their musical instruments. And they played these long chords, with interesting rhythmic patterns, and everyone sat in the dark, the place was packed and everyone sat in the dark and were just carried away by this music and so was I. And afterward, I meant them and I didn’t even know I was going to do this movie, but I said to them “Look, when I do my next film, I want you guys to do the score. When I get the script, I’ll sent it to you, and I’ll tell you what it’s about, when I figure that out, but I don’t want you to see the film; I don’t want you to see the movie and write a score to the movie. I want you just to create a score from what I tell you about it, and from the script.” And that’s what they did. And when we were in Mexico, doing the bridge scene, in the Mexican jungle, a bunch of tapes arrived, and it was their score. And then along with the editors, I fit the score to the film. I was inspired in the editing of the film by the music. I was inspired the music, instead of having the film scored.

SF: I have you worked that way on other films too?

WF: Pretty much, ya. And I don’t really decide what I’m going to do- when you’re in the cutting room, the film speaks to you. And there are 3 phrases in making a film, at least 3: There’s the story and screenplay phrase, there’s shooting it, and then in the editing room it’s a completely different experience. The film is all there and all shot, and it’s just waiting to be assembled and it speaks to you. Sometimes- there were 9 scenes that I shot for The French Connection, and took out of the film. Because in those days, you know we used to splice film by hand and then you’d look at every cut and I’m telling you, I would make some cuts and it were though the film were screaming at me, “No! This doesn’t work! I am not this, I am that!” And with The French Connection I had 9 scenes that were about character and the film didn’t want them. It was a chase movie, and that’s all it wanted to be and it was telling me that constantly. And I remembered That (F.) Scott Fitzgerald had a little card on a bulletin board over his typewriter in which he had written “Action is character”. And I always thought about that. The idea in this great novel, The Great Gatsby, he says action is character, meaning you don’t have to explain who a character is, what they do is who they are. And I always kind of looked for things that fulfill that in the films that I’ve made. So, this film had a lot more dialogue originally, it had other scenes, but it didn’t want them, it rejected them in the cutting room. And in the editing process, you pay attention to what the film is saying to you and it is speaking to you. And a lot of my films- take for example Cruising, changed completely in the editing room.

SF: I want, before you take questions from the audience, I want to just ask you a little about the decision to write a memoir, and what that process was like for you because I think one of the things that surprised me about the book is that you were quite hard on yourself at a lot of points, particularly talking about this film, and some of the things you were saying earlier about your ego, about the decision not to use Steve McQueen, you’re dealing with the studio, and the period immediately following this film. It is a kind of story of hubris, and bad decisions, a lot of it and ultimately the end is this great second act you’ve had with opera and the dependent films you’ve done. It feels like it was very cathartic to write…

WF: Ya, it does feel like it was carthartic, but it wasn’t. (big laugh) I had a call out of the blue about almost 4 years ago from a man name Richard Pine and he runs and author’s agency in New York called Inkwell Management. I had never heard him or Inkwell Management. But he said, “Listen, are you interested in writing a memoir?” And I say “no”. He said, “Why not?” I said “because I wouldn’t be interested in reading it.” (laugh) He said “What if I were to tell you that I had 5 publishers in New York, leading publishers, who would publish your memoir that you wrote.” I said “that would get my attention, certainly.” So I came to New York, I met with these 5 gentlemen and it was the publisher from HarperCollins that I said “Look, I wouldn’t even know where to begin. I never kept diaries, I never kept any of my notes I ever made, sketches for any of the scenes that I shot, and most importantly, I have no diaries.” He said “Look, I would suggest that you do not write a book were you just say, ‘this happened’, and ‘this happened’ and ‘this happened’; write about your feelings about everything you can remember that was important to you.” And that was important to me. And that opened the door to me- that it was about feelings, more than events. The events are there, but it is how I felt about them at the time. And that’s what got me going on it. I wrote the book in long-hand, over 3 years and I would sit down somewhere on a set, or in a hotel room or on an airplane, or at home- whatever and I would just start to think about things, and things would come to me. And I would write about them, until I lost the thread, and then the next day I would write about something else. And then eventually, I would remember something else, about those things that I had written, and I would add to it. And when I had a lot of it hand-written, I went talked to a lot of the people I had worked with- Billy Blatty, who wrote The Exorcist, and Norman Lear, and any number of people that I had worked with to get their impressions and I was finally able to pull it together. It took over 3 years of writing and uh, it wasn’t cathartic, but I did decide to tell the absolute truth in this book, as I remember it. And without censoring myself or editing myself, and as you say, I don’t go easy on myself, I don’t blame anybody for the mistakes I may have made. And I give credit where credit is due: all of the people who’ve worked with me because it is there films too. Any of you who ever made a film, or anything like it, know that it’s definitely a collaborate medium, in the highest sense of the word.

WF: Ya, it does feel like it was carthartic, but it wasn’t. (big laugh) I had a call out of the blue about almost 4 years ago from a man name Richard Pine and he runs and author’s agency in New York called Inkwell Management. I had never heard him or Inkwell Management. But he said, “Listen, are you interested in writing a memoir?” And I say “no”. He said, “Why not?” I said “because I wouldn’t be interested in reading it.” (laugh) He said “What if I were to tell you that I had 5 publishers in New York, leading publishers, who would publish your memoir that you wrote.” I said “that would get my attention, certainly.” So I came to New York, I met with these 5 gentlemen and it was the publisher from HarperCollins that I said “Look, I wouldn’t even know where to begin. I never kept diaries, I never kept any of my notes I ever made, sketches for any of the scenes that I shot, and most importantly, I have no diaries.” He said “Look, I would suggest that you do not write a book were you just say, ‘this happened’, and ‘this happened’ and ‘this happened’; write about your feelings about everything you can remember that was important to you.” And that was important to me. And that opened the door to me- that it was about feelings, more than events. The events are there, but it is how I felt about them at the time. And that’s what got me going on it. I wrote the book in long-hand, over 3 years and I would sit down somewhere on a set, or in a hotel room or on an airplane, or at home- whatever and I would just start to think about things, and things would come to me. And I would write about them, until I lost the thread, and then the next day I would write about something else. And then eventually, I would remember something else, about those things that I had written, and I would add to it. And when I had a lot of it hand-written, I went talked to a lot of the people I had worked with- Billy Blatty, who wrote The Exorcist, and Norman Lear, and any number of people that I had worked with to get their impressions and I was finally able to pull it together. It took over 3 years of writing and uh, it wasn’t cathartic, but I did decide to tell the absolute truth in this book, as I remember it. And without censoring myself or editing myself, and as you say, I don’t go easy on myself, I don’t blame anybody for the mistakes I may have made. And I give credit where credit is due: all of the people who’ve worked with me because it is there films too. Any of you who ever made a film, or anything like it, know that it’s definitely a collaborate medium, in the highest sense of the word.

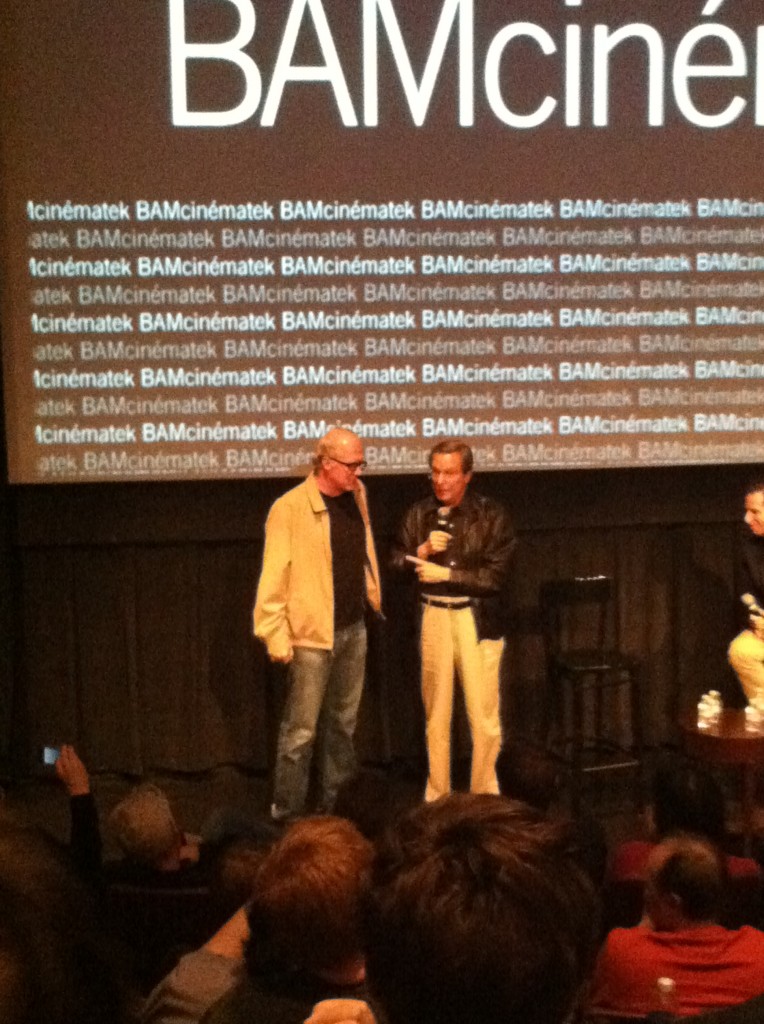

William Friedkin & Tracey Letts

SF: Now I would be amiss if I didn’t point out that there is one film of yours that is not mentioned at all in the book, which is The Guardian.

WF: Well there’s two. I didn’t remember a lot about that film and I didn’t think people would want to read about an absolute and complete disaster (laugh). And, you know, you gotta take some stuff out. I mean, I knew I was not going easy on myself but the people who buy this book are mostly gonna want to read about The Exorcist, or The French Connection. So I’m not that stupid (laugh), I’m not gonna write about a film that was take to Guantanamo and forgotten. (lingering laugh) Are you going to take questions? (laugh)

SF: Yes-

WF: Before you do, there are two people I’d like to introduce you to. I would be very amiss if I didn’t bring up here to say hello, a man who, not only has one a Pulitzer Price, but a Tony Award for his great play August: OSage County, be he has also written for me, two of the films I’m most proudest of, Killer Joe and Bug, he’s know, believe it or not be may the only such person that is nominated for a Tony Award as best actor for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, I like you to say hello to Tracey Letts. (applause) This guy is the real deal. You wanna say anything?

Tracey Letts: Wow, what a great movie, what a great film. A beautiful, beautiful picture.

WF: I got that $20 for you outside (big laugh) Now, I’d like to also introduce your costar in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? who has also nominated for a Tony Award, Carrie Coon (applause).

Carrie Coon: Wow what a great movie, that was really a beautiful picture. (laugh)

Friedkin w/ Letts & Carrie Coon

WF: $10 more for you. (laugh) Have you guys seen Virginia Woolf? (big applause) Well, in his case, to be able write like that and also act like that, is absolutely stunning. And (to Coon) you own that part now. You guys are wonderful and I appreciate you coming tonight, and thanks for coming up here. (big applause) Oh, and one more second. Is Randy Jurgensen here tonight?

Dion Baia: No he’s not.

WF: How come?

DB: He flew out, was traveling early this morning.

WF: Ok. He is a very interesting guy in my life, he is the guy in the last close up in the film, he’s the guy that comes after Scheider at the end. He was a Detective on the New York City Police Department for many years, and he’s the guy that went undercover into the S&M bars to find the killer that was one of the inspirations for Cruising. And he said he was coming tonight… coward (big laugh). He is one of the greatest street cops I’ve ever met.

SF: There’s another interesting Cruising connection that if I remember correctly, the guy who was accused of those murders, was an actor in The Exorcist.

WF: He wasn’t an actor. His name is, or was Paul Bateson, I don’t know what his name is now, but he in The Exorcist for those of you who have seen it, there’s a scene where they’re at NYU Medical Center where they’re performing an Arteriogram on the little girl. And I used an actual Neurosurgeon and his male nurse. And the male nurse was a guy named Paul Bateson, and about 5 years after The Exorcist, I opened the New York Daily News and saw his picture on the front page. He was accused of these so-called “CUPPI” murders that were occurring in the S&M bars in lower Manhattan. “CUPPI” meant that there were body parts in drawers in the morgue, and the body parts were called “CUPPI’s”, which meant Circumstances Unknown, Pending Police Investigation. And there were several of these murders; body parts dragged in from the East River and Paul Bateson was accused of the murders. So I called his lawyer, whose name was in the paper, and asked if I could see Paul. And I went to Rykers Island and saw him and interviewed him and he told me about the one particular murder they got him on. They actually got him because when he was cutting guys up, and throwing their body parts- he threw them into big plastic bags… and the bags had little small print on them that said NYU Medical Center (audience gasps) Psychiatric Ward. (laugh) And that’s how they got Paul, and uh, the first thing he said to me when I went in to the room and saw him was “How’s the picture doing?” (big laugh) I said “It’s doing very well”, it was still playing, “It’s doing very well Paul… Did you do these murders?” (big laugh) “I think I remember one I did, but the others, I was so high, that I don’t really remember.” And he gave me all the facts and all the details from his perspective and then Randy Jurgensen gave me the rest from his perspective, and then there was a brilliant writer from the Village Voice named Arthur Bell, who wrote a series of articles about these clubs, and they were sort of warning shots, because there were all these murders, at the time in the S&M clubs, and then there were mysterious deaths, that did not have a name. A year or so later they had a name- it was AIDS (audience sigh), and Bell wrote very cautionary tales about what was going on there. It’s all yours Scott.

Q1: I read somewhere that Sorcerer was the movie you were most proud of because virtually everything you see on screen was exactly the way you wanted it to be- do you still hold to that claim to this day?

WF: I’m not sure if I would say proud of, I would say I have strong feelings about it because the only way that I can think about a film is how close I came to what I had in mind. You know, you can’t make a film thinking “geeze, what will the critics say? I wonder what Scott, or the other critics might say?” You can’t go in expecting that or thinking that, and you don’t know how an audience is going to react to anything you do. The only thing- and you can’t really sit in judgment of your own work because you’re too close to it. What I will say is this was the hardest film I ever had to make, by far. We had to do all this stuff-there was no CGI- you know what CGI is don’t you? (big laugh) That’s all you need right now to make a film. All you need to know is CGI: Computer Generated Imagery. But we didn’t any of that- everything you see in this film, we had to do. There are no opticals, uh, we had to so everything that’s in the picture, and that made the process a lot of fun. But it was life-threatening (laugh), half of the crew either got malaria or gangrene, (laugh) including me. I was out for a very long time…

SF: Where do we sign up? (Laugh)

WF: Right… McQueen was right! I should of done the film in America! Malibu Beach could have been the place. Thank you for that question.

Q2: The film is tremendous and I’ve waited a long time to see it and I really can’t add to anything beyond what you just articulated, I have also waited a long time to ask you a question which, to hear your side of the story. This was told to me when I was a child- I met Marty Feldman, may he rest in peace, and my father asked him, “Mr. Feldman, why at the Oscars did you throw an Oscar to the floor and break it?” And he said to my father and I: “Billy Friedkin asked me to do it!” and I wanted to know if such a story was true?

WF: That’s absolutely true. (Big laugh and applause) I produced the Academy Awards, I think it was ’78 or ’77, it was the year Rocky and Network were head to head for the Academy Awards and I was asked to produce it. ’77 or ’76… And the head of the Motion Picture Company implored me to produce to Academy Awards and I had just come back from Sorcerer, and I decided to use more women on the show than they ever had, more African Americas, and a lot of radicals. I had Norman Mailer presented the best screenplay (laugh). I had Lillian Hellman present the best documentary- these were people who were like blacklisted in Hollywood- (laugh) they didn’t want Lillian Hellman or Norman Mailer. And I can only say I admired these people; and part of it was my arrogance, but I admired Mailer and a lot of people like that, and I decided to have fun with the show because I thought then and still think that it isn’t a lot of fun. You sit there for 3 and a half hours listening to lame jokes being read off a teleprompter, and often the film that wins is forgotten next year. Or you know when you think that Citizen Kane did not win the Academy Award; you just throw up your hands and say: “what value is it then?” What value it has is it is the greatest hype an industry has ever created for itself. (laugh) You know if the auto industry had invented a hype like that, they might be solvent. (laugh) So I had a lot of fun with it, and I had Red Skelton come on dressed as a clown and give the best clown award. And I brought on Marty Feldman– do any of you remember Marty Feldman? (big applause) A lot of Jewish people in the audience (big laugh) We made Marty Feldman a fake Academy Award that looked real, and he brought it on very carefully, and just before he presented it, he dropped it to the floor. I must have had 50,000 letters denouncing me for that. If there had been Facebook or Twitter, I might have been hung (laugh). He turned out to be something people didn’t appreciate. But I tried to have a lot of fun with that show. We actually opened the show, I figure it was edited afterwards, I opened the show, not on the dress parade that usually precedes the Academy Awards, and I opened the show on a close up on Richard Pryor. (big laugh) You said- looked into the camera- and said, “No Black man has ever won nuthin’ for anything” (big laugh and applause). And that was the opening line, (applause) at the Academy Awards… Richard was going to use the N word, and I said “Go ahead Richard” because (Big laugh) he was known for that, (big laugh) Do it! He changed it at the last minute and said “no Black man”. So that’s how the show started, so you can imagine how it ended up. And Rocky won Best Picture to a lot of people’s shock and surprise. The other thing I did on that show was take out the word “Best” because I didn’t believe it and I still don’t. we didn’t call it the Best Picture, the Best Screenplay, Best Sound whatever, I just had the host say “The Academy Award for an Original Screenplay; or an Academy Award for an Adapted Screenplay; the Academy Award for the Direction of a Featured Film. Not ‘best’. And at the end, I had Warren Beatty come out and he explained why we took the word ‘Best’ out of the ceremony, because the people who make films really don’t think that they’re in competition with anybody else. It’s not a competition. A tennis match is a competition; a prize fight, whatever- films or not in competition with one another. (Applause)

WF: That’s absolutely true. (Big laugh and applause) I produced the Academy Awards, I think it was ’78 or ’77, it was the year Rocky and Network were head to head for the Academy Awards and I was asked to produce it. ’77 or ’76… And the head of the Motion Picture Company implored me to produce to Academy Awards and I had just come back from Sorcerer, and I decided to use more women on the show than they ever had, more African Americas, and a lot of radicals. I had Norman Mailer presented the best screenplay (laugh). I had Lillian Hellman present the best documentary- these were people who were like blacklisted in Hollywood- (laugh) they didn’t want Lillian Hellman or Norman Mailer. And I can only say I admired these people; and part of it was my arrogance, but I admired Mailer and a lot of people like that, and I decided to have fun with the show because I thought then and still think that it isn’t a lot of fun. You sit there for 3 and a half hours listening to lame jokes being read off a teleprompter, and often the film that wins is forgotten next year. Or you know when you think that Citizen Kane did not win the Academy Award; you just throw up your hands and say: “what value is it then?” What value it has is it is the greatest hype an industry has ever created for itself. (laugh) You know if the auto industry had invented a hype like that, they might be solvent. (laugh) So I had a lot of fun with it, and I had Red Skelton come on dressed as a clown and give the best clown award. And I brought on Marty Feldman– do any of you remember Marty Feldman? (big applause) A lot of Jewish people in the audience (big laugh) We made Marty Feldman a fake Academy Award that looked real, and he brought it on very carefully, and just before he presented it, he dropped it to the floor. I must have had 50,000 letters denouncing me for that. If there had been Facebook or Twitter, I might have been hung (laugh). He turned out to be something people didn’t appreciate. But I tried to have a lot of fun with that show. We actually opened the show, I figure it was edited afterwards, I opened the show, not on the dress parade that usually precedes the Academy Awards, and I opened the show on a close up on Richard Pryor. (big laugh) You said- looked into the camera- and said, “No Black man has ever won nuthin’ for anything” (big laugh and applause). And that was the opening line, (applause) at the Academy Awards… Richard was going to use the N word, and I said “Go ahead Richard” because (Big laugh) he was known for that, (big laugh) Do it! He changed it at the last minute and said “no Black man”. So that’s how the show started, so you can imagine how it ended up. And Rocky won Best Picture to a lot of people’s shock and surprise. The other thing I did on that show was take out the word “Best” because I didn’t believe it and I still don’t. we didn’t call it the Best Picture, the Best Screenplay, Best Sound whatever, I just had the host say “The Academy Award for an Original Screenplay; or an Academy Award for an Adapted Screenplay; the Academy Award for the Direction of a Featured Film. Not ‘best’. And at the end, I had Warren Beatty come out and he explained why we took the word ‘Best’ out of the ceremony, because the people who make films really don’t think that they’re in competition with anybody else. It’s not a competition. A tennis match is a competition; a prize fight, whatever- films or not in competition with one another. (Applause)

Q3: You mentioned in both Wages of Fear and Sorcerer, theme was really the key component when you were looking at the original to remake it, and it’s clear how much time you took to show these are not just nefarious guys, but they’re also murderers, they’re terrorists- very nefarious, and then the events pay out almost the same, but in Wages of Fear they’re painted as saints that struggle and come out at the end, with the one guy who survives in Clouzots, and in this you are watching bad guys trying to survive- so what does that say about how you view the theme of both films?

WF: Uh, I view the theme of both films as being quite similar, but I told you up front that I changed the characters. I wasn’t interested in angels or heroes. I believe there is good and evil in everyone in this audience and everyone on the planet. I don’t believe in perfect people, or superheroes, I just don’t. There are many heroic deeds done every day, many of them unsung. But I wasn’t interested in promoting the idea of an angel, or saint to use your word, or superhero; I wanted flawed guys to go through this adventure. As they are for example in this wonderful play by Reginald Rose that I did for television called 12 Angry Men, those are all flawed people, deciding the fate of a young man, who is on trial for murder. And all of their flaws come out in the course of this magnificent drama. So, I tend to not believe in heroes or villains, but a little bit of both in everyone. Perhaps a young woman has a question? Yes.

Q4: You’re film has a lot of funny moments, which I wasn’t expecting. Was that something you thought about in the writing or was that something that came out in production?

WF: We didn’t try to make anything funny; (laugh) I mean there are no jokes, (laugh) but there is a sense that occurs that people tend to laugh about certain things whenever they can in a film; especially a serious film, where you need some relief from what’s going on up there. The audience wants to laugh and will sometimes laugh in inappropriate places and I understand that. There are huge laughs in The Exorcist (laugh), and believe me they are not intended (big laugh), but they’re usually followed by somebody passing out in the chair. But no, those lighter moments did we think of as being that, but you do find that out going to screenings. Audiences need that relief. If you don’t provide it, you will yourself provide it.

SF: We have time for one more.

Q5: How do you deal with the moment when you’re watching a film of yours and realizing it is not what you had in mind?

WF: That is a real great question. It-it’s bad. (laugh) You know, I could say to you, “Shit- I don’t care.” But that would be a lie. No, that’s what really bothers me and it’s sometimes I’ve become ill over that. When you make a film, you don’t do it alone, obviously, but there is usually one particular intelligence, that forms a film, that decides what it’s going to be. The themes, the story, the dialogue, the actors, so it’s a creation like anything else, even though you’re not working alone, you’re working with others. But you take a proprietary interest- and believe me, the people I’ve worked with on the crews feel the same, when a film doesn’t work out to our expectations. You’re- you’re blown away, it’s bad, it’s a terrible feeling. Can you imagine how Vincent Van Gogh must of felt when he couldn’t sell one fucking painting (laugh)? You know? And now he’s considered the greatest artist of all time. One night I came back late to my apartment in New York and I turned on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, who said the following: “A painting sold at auction today for the highest price a painting as ever sold for.” And of course it was a Vincent Van Gogh. And he said, “What must people don’t know is that when Van Gogh made this painting, he was in a mental institution. And the reason he was in a mental institution was because he said ‘One day, I’m going to sell a painting for $80 million!’”. Can you imagine how that guy felt? Or Vermeer? You can’t buy a Vermeer– there is only something like 37 of them. You can’t buy a Vermeer for any amount of money today, not even if you are a Russian billionaire. They’re just not for sale. And when Vermeer died at a very young age, he died broke. And there was a custom in Delft, where he lived, where someone died, the city fathers would come around and collect their clothing and donate it to the poor. Vermeer’s clothes were so bad, they burned them. His wife was out selling his canvases out in the streets for a few guilders, and now… you know. And then I think about Orson Welles, and Citizen Kane, who made what I think, the most influential picture and most profound film ever made. And by the way, yesterday was the anniversary of the opening of Citizen Kane at the RKO Palace in downtown New York; in 1941- it opened May 1st, 1941. And that’s the reason I became a film director. I had no idea of becoming a film director until I saw that picture. And I couldn’t believe what a great work of art this was, and it was even possible to achieve something like that. And I never have, and I never will, and I’ve had to- (audience sigh) Ya! (big laugh) Don’t say The French Connection! I’m not fit to tie Orson Welles’ shoe laces, wherever the hell they are! (big laugh) And he made probably the most influential film ever and it got a wonderful and critical reception, and was a financial failure. And after you realize that, you get a different perspective on your own work; unless you’re Vincent Van Gogh and never saw Citizen Kane. What?

Audience Member: Ingmar Bergman used to watch James Bond to fall asleep…

WF: I would too! (big laugh) He enjoyed them. I enjoy them- I enjoy them. There’s nothing wrong with that.

AM: The audience goes to see them to get pleasure right?

WF: Uh. The audience goes most to have pleasure, you’re absolutely right; to have some sort of relief, to have some sort of escape, no matter what the film is. And that has to be taken into account by the filmmakers. And often I did not take that into account. But often, I don’t know how to do that. (the audience sighs in acknowledgement) No, no- not really. I mean today, the zeitgeist has shifted completely. I have no idea what you guys are watching. I couldn’t watch The Avengers, you know, if I could get off of double-murder. (big laugh) I tried to do that, but I can’t. And there’s nothing wrong with it, it’s me! (laugh) I just don’t get it. So, we all have our own tastes and our own sense of what is pleasurable and what isn’t. To me, it’s to give the audience some involvement in the story; which might not always be pleasurable. But, the worst thing any of you could say about this film, to me, is “Geeze, it was really interesting.” (big laugh) That’s the worst thing I’ve ever heard! You could say “what a piece of shit!” (big laugh) or like some of you said, that this is great, and that does move me. But interesting?! Who the hell goes to the movies for interesting? You watch Fox News for interesting! (big laugh) You read the New York Post for interesting! No? I don’t care what Ingmar Bergman watches at night! (big laugh and applause) I’m more interested what Ingrid Bergman saw at night!!

William Friedkin & Dion Baia

The Podwits would like to thank BAM, Scott Foundas, and certainly the great William Friedkin for this very rare opportunity to hear him talk shop and for giving us his masterpiece, Sorcerer! We can’t wait for the Blu Ray release!!!

[…] (5/13/13): A transcript of the Q&A can be found here. At some point I’ll prepare a downloadable PDF of […]